The

turtle, the librarian and the Barbie dolls

The life of a demented and bigoted hypochondriac

provides Jonathan Miller with an unlikely triumph. But hurry - only 55

of you can see it at a time

Kate

Kellaway

Observer

Sunday

May 26, 2002

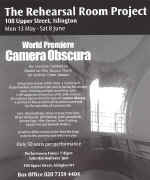

Camera

Obscura Almeida rehearsal rooms, London N1

Arthur

Inman wrote 17 million words. He wrote about a life that wasn't a life.

This eloquent, bigoted, demented American diarist put himself under

hotel arrest for decades - he suffered from extreme hypochondria - and,

like a literal Yankee cousin to Proust, wrote about America and

everything that did and didn't happen behind the drawn curtains of his

room.

Arthur

Inman wrote 17 million words. He wrote about a life that wasn't a life.

This eloquent, bigoted, demented American diarist put himself under

hotel arrest for decades - he suffered from extreme hypochondria - and,

like a literal Yankee cousin to Proust, wrote about America and

everything that did and didn't happen behind the drawn curtains of his

room.

Was his mighty tome his tomb? He yearned for

publication, perhaps as a projected end to loneliness. He sought young

women, too. He would advertise for them to read and talk to him - and

would fondle or sometimes have sex with them - and record this as

compulsively as he did everything else. He kept his diaries between 1918

and 1963, the year he shot himself.

On the face of it, this would not seem like a subject

for a play: static, verbose, disagreeable. But Camera Obscura is

a fantastic

piece, written by Lorenzo DeStefano and meticulously directed by

Jonathan Miller.

On the face of it, this would not seem like a subject

for a play: static, verbose, disagreeable. But Camera Obscura is

a fantastic

piece, written by Lorenzo DeStefano and meticulously directed by

Jonathan Miller.

It is out of the ordinary in every way. For a start, it

is being performed in the Almeida's rehearsal rooms which seat only 55

people. This almost removes the sense of being at the theatre; there is,

instead, a feeling of disquieting involvement.

We are in the dark, watching occasional, forbidden light

(Inman abhored the sun) falling across a room that, at times, recalls an

Edward Hopper interior, complete with an atmosphere of tense

irresolution. The unexpectedly robust pleasure of the evening is in

trying to make sense of Inman's psychology.

I

revelled, too, in the language, which is as agile as Inman himself is

immobile. He hazards weird, decadent generalisations. He seldom has an

ordinary response to anything. He looks like a cross between a turtle

and Oscar Wilde, beached high on his hospital bed with whisky, pink

pills, girls who resemble Barbie dolls and an uncanny wife - Evelyn - as

his companions.

I

revelled, too, in the language, which is as agile as Inman himself is

immobile. He hazards weird, decadent generalisations. He seldom has an

ordinary response to anything. He looks like a cross between a turtle

and Oscar Wilde, beached high on his hospital bed with whisky, pink

pills, girls who resemble Barbie dolls and an uncanny wife - Evelyn - as

his companions.

Evelyn (Diana Hardcastle) is as hard to fathom as he is.

She looks like an elegant, sauntering librarian, dressed in black, as if

registering her husband's living death (after his suicide, she switches

to cream). She is a fashion plate, a bemusing combination of infidelity

and devotion. Inman has a harsh, comic instinct, telling her at one

point: 'You look like you're getting all your exercise writing cheques.'

Other visitors come and go, like flies alighting on a

decaying fruit. His interest, he more than once maintains, is in the

hidden and the unseen. This becomes our concern, too, as we consider him

in darkness and in a posthumous limelight.

Camera Obscura, The Almeida Rehearsal

Room, London

In bed with Arthur Inman

Review by Paul Taylor

27 May 2002

The

tables have been turned on the excellent actor Peter Eyre. Earlier this

year, as Kenneth Tynan paying court to Louise Brooks in Smoking with

Lulu, he played the visitor of a legendary recluse. Now, in Lorenzo

DeStefano's fascinating play Camera Obscura, he plays the

legendary recluse who is being visited, skilfully switching from bedside

to in-bed manner.

The

tables have been turned on the excellent actor Peter Eyre. Earlier this

year, as Kenneth Tynan paying court to Louise Brooks in Smoking with

Lulu, he played the visitor of a legendary recluse. Now, in Lorenzo

DeStefano's fascinating play Camera Obscura, he plays the

legendary recluse who is being visited, skilfully switching from bedside

to in-bed manner.

The show is based on the real-life diaries of Arthur

Crew Inman (1895-1963), a moneyed American who made a kind of art form

of his phobias (to light, noise, John F Kennedy etc) and took the

principle

of room service to quite extraordinary lengths. Unwilling to leave his

darkened apartment in the Garrison Hall hotel, in Boston, where he had

bought all the neighbouring flats in a doomed effort to eliminate

disturbance, he advertised in the press for "talkers" to tell

him the story of their life. Some of the females who responded were

fondled; others had full sex. The diaries therefore became an informal

and unpublished Kinsey report avant la lettre. His live-in wife

put up with his behaviour.

The show is based on the real-life diaries of Arthur

Crew Inman (1895-1963), a moneyed American who made a kind of art form

of his phobias (to light, noise, John F Kennedy etc) and took the

principle

of room service to quite extraordinary lengths. Unwilling to leave his

darkened apartment in the Garrison Hall hotel, in Boston, where he had

bought all the neighbouring flats in a doomed effort to eliminate

disturbance, he advertised in the press for "talkers" to tell

him the story of their life. Some of the females who responded were

fondled; others had full sex. The diaries therefore became an informal

and unpublished Kinsey report avant la lettre. His live-in wife

put up with his behaviour.

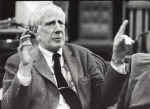

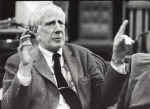

The photo of a testy-looking, toothbrush-moustached

Inman in the programme suggests a peppery, wired-up individual.

Eschewing impersonation, Peter Eyre converts the character into a great

tragicomic creation, his

demeanour reminding you more of the flabby Wilde, and his seductively

low-key Southern drawl, of a Tennessee Williams faded belle. The

dimpling, little-boy bids for pathos are as outrageously manipulative as

his innocent-seeming curiosity when he's pruriently quizzing his lady

visitors about the precise sensations felt during the female orgasm.

There's something at once floppily invertebrate and strong-willed about

this whisky-swigging, politically bigoted self-made invalid who takes

such a calculatedly childish delight in tape-recording every

embarrassing session. To be goosed by him would be like being molested

by a tenacious blancmange.

The photo of a testy-looking, toothbrush-moustached

Inman in the programme suggests a peppery, wired-up individual.

Eschewing impersonation, Peter Eyre converts the character into a great

tragicomic creation, his

demeanour reminding you more of the flabby Wilde, and his seductively

low-key Southern drawl, of a Tennessee Williams faded belle. The

dimpling, little-boy bids for pathos are as outrageously manipulative as

his innocent-seeming curiosity when he's pruriently quizzing his lady

visitors about the precise sensations felt during the female orgasm.

There's something at once floppily invertebrate and strong-willed about

this whisky-swigging, politically bigoted self-made invalid who takes

such a calculatedly childish delight in tape-recording every

embarrassing session. To be goosed by him would be like being molested

by a tenacious blancmange.

Yet the play and the performance help you to see why so

many people remained loyal to him – not least his wife, whose

oscillation between exasperated affection and the desperate desire for

some freedom and dignity is beautifully captured by Diana Hardcastle.

The hypochondriac's gently insistent air of total entitlement would very

quickly, you feel, enslave anyone without his paradoxical strength of

character. But that manner covers a terrible

pathos.

Yet the play and the performance help you to see why so

many people remained loyal to him – not least his wife, whose

oscillation between exasperated affection and the desperate desire for

some freedom and dignity is beautifully captured by Diana Hardcastle.

The hypochondriac's gently insistent air of total entitlement would very

quickly, you feel, enslave anyone without his paradoxical strength of

character. But that manner covers a terrible

pathos.

The play is shaped in the life-in-the-day-of format, and

it happens to be the day, in 1963, on which he took his own life. The

consequences of his warped manner of existence crowd in on him. Through

a succession of encounters, which the expert shading of Jonathan

Miller's production prevents from ever feeling like a desultory straggle

of

visits, Inman makes some painful discoveries. He forces his wife into

revealing her 30-year affair with his doctor and friend, Cyrus Pike

(Jeff Harding). His sinister, Orton-esque Dutch manservant (Richard

Brake) turns out to have passed on one of the incriminating diaries to

his landlords, raising the threat of eviction from his

cocooned redoubt. And not just the living come to pay their disrespects.

Causing him to curl up in a foetal heap, his cotton-baron father pops

back from the dead to remind Inman of his vain attempts to become a

poet, derisively quoting the awful doggerel and its vicious reviews.

The play is shaped in the life-in-the-day-of format, and

it happens to be the day, in 1963, on which he took his own life. The

consequences of his warped manner of existence crowd in on him. Through

a succession of encounters, which the expert shading of Jonathan

Miller's production prevents from ever feeling like a desultory straggle

of

visits, Inman makes some painful discoveries. He forces his wife into

revealing her 30-year affair with his doctor and friend, Cyrus Pike

(Jeff Harding). His sinister, Orton-esque Dutch manservant (Richard

Brake) turns out to have passed on one of the incriminating diaries to

his landlords, raising the threat of eviction from his

cocooned redoubt. And not just the living come to pay their disrespects.

Causing him to curl up in a foetal heap, his cotton-baron father pops

back from the dead to remind Inman of his vain attempts to become a

poet, derisively quoting the awful doggerel and its vicious reviews.

And yet this failed artist, this Proust

without the excuse of a great novel, left a vast literary legacy: 17

million words in 155 volumes of diaries. It can only be a compliment to

the play, production and cast that they have left me avid to get hold of

the published extracts.

To 8 June (020-7359 4404)

Diary

of a nobody

How did a housebound hypochondriac write a 17

million-word journal? And why has Lorenzo DeStefano turned it into a

play?

Lorenzo

DeStefano

Guardian

Wednesday

May 8, 2002

Why

bother, one could ask, with the rantings of a semi-invalid holed up in a

crumbling apartment hotel in a dying American city? What use are his

unsolicited opinions on world affairs, his ambitions for literary

immortality, his calcified Victorian ideas on race and natural

selection, his obsession with young girls? In the case of Arthur Crew

Inman, I found his ramblings very useful indeed - once I had overcome my

initial revulsion in order to look further into his self-made shadow

land.

Why

bother, one could ask, with the rantings of a semi-invalid holed up in a

crumbling apartment hotel in a dying American city? What use are his

unsolicited opinions on world affairs, his ambitions for literary

immortality, his calcified Victorian ideas on race and natural

selection, his obsession with young girls? In the case of Arthur Crew

Inman, I found his ramblings very useful indeed - once I had overcome my

initial revulsion in order to look further into his self-made shadow

land.

I first encountered the 17 million-word diary of this

transplanted resident of Boston in 1985, the year Harvard University

Press published a two-volume set entitled The Inman Diary: A Public and

Private Confession. Edited over a seven-year period by Daniel Aaron, a

professor of American literature at Harvard, Inman's diary easily

qualifies as the longest ever written by an American and perhaps by any

citizen of any land.

I first encountered the 17 million-word diary of this

transplanted resident of Boston in 1985, the year Harvard University

Press published a two-volume set entitled The Inman Diary: A Public and

Private Confession. Edited over a seven-year period by Daniel Aaron, a

professor of American literature at Harvard, Inman's diary easily

qualifies as the longest ever written by an American and perhaps by any

citizen of any land.

Covering the years 1903-63, Inman's social observations

range from his favourite subject, the American civil war, through the

onset of the nuclear age up to the assassination of John F Kennedy. It

becomes clear early on that this failed romantic poet meant these vast

outpourings to ensure him the kind of literary fame that eluded him

during his sleepless days and nights in apartment 604 at Garrison Hall,

the building he hardly left for 50 years. His desire for the spotlight

rears its head throughout the diary.

"I wish there was a way I could know right now

whether it's been worth the immense effort and nervous perseverance I've

spent trying to maintain the highest quality of this work, its honesty.

If the diaries of Pepys, Casanova, Boswell and Rousseau have proven of

interest to future generations, why not mine?"

Some

would say that this is inordinately high company for a scribbling nobody

to keep, even in his own mind. And yet, taken as a whole, The Inman

Diary stands up quite well alongside those great chroniclers. While one

quickly tires of his endless hypochondriacal moanings - "right

thumb sprained, coccyx badly bruised, both arms a constant useless

agony. What a bruised, squirming semblance of a thing I am" - it is

the truly democratic nature of Inman's diary that most impresses me.

Some

would say that this is inordinately high company for a scribbling nobody

to keep, even in his own mind. And yet, taken as a whole, The Inman

Diary stands up quite well alongside those great chroniclers. While one

quickly tires of his endless hypochondriacal moanings - "right

thumb sprained, coccyx badly bruised, both arms a constant useless

agony. What a bruised, squirming semblance of a thing I am" - it is

the truly democratic nature of Inman's diary that most impresses me.

Instead of the self-centred epic of the mind that it

threatens to become, the work is radically transformed by the people

Arthur met after moving to Boston in November 1919. By placing personal

ads in the city's papers for over 40 years, he reached well beyond the

confines of apartment 604 to a surprisingly diverse and fascinating

range of fellow humans.

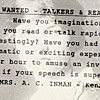

"Wanted: Talkers & Readers - Have you

imagination? Can you read or talk rapidly and interestingly? Have you

had unusual, dramatic or exciting experiences? $5.00 per hour to amuse

an invalid author (more if your speech is superlative)."

By including the hopes and dreams of the anonymous

shopgirls and clerks and travelling salesmen who responded to

his lure in great numbers, Inman broadened the scope of his work without

a thought for social rank or educational accomplishment. What interested

him most was a cracking good story well told, the effluvia of lives he

could barely imagine on his own.

By including the hopes and dreams of the anonymous

shopgirls and clerks and travelling salesmen who responded to

his lure in great numbers, Inman broadened the scope of his work without

a thought for social rank or educational accomplishment. What interested

him most was a cracking good story well told, the effluvia of lives he

could barely imagine on his own.

"At last count I have chronicled the lives of more

than 1,000 people within these pages. They are not what you'd call great

people. For the most part they are of the common, everyday variety. Yet

they are far more interesting to me than persons of wealth or so-called

"class"."

By pursuing his passion for recording the passage of

time, Inman meant to ensure not only himself but these fellow citizens a

measure of the immortality he felt they all deserved. Of course, the

diary's eventual publication 22 years after his death was nothing but a

distant hope throughout his long, unquiet life.

"I wish to explain, in the unlikely case that this

diary should ever be deemed to amount to more than the paper it is put

upon, the broad theory of its organisation... I delve back into my past

and set down all the odds and ends I can remember, so that in the

fullness of time I shall have painted the parts of a connected frieze,

parts of which you, dear readers of the future, will have to put

together."

And

so I did. With Daniel Aaron's expert guidance, a design began to emerge.

Absorbing this diary - overwhelming in scope, yet delicate in nature -

was like plunging head first into a frigid pool. Daunted at first by its

sheer size (1,600pages even in its abridged form), I swam on, pulled

forward through each entry by the emerging voice. Almost every one

hinges upon Inman's opinions on everything from the price of soap to the

bloated reputation of one of his favourite enemies, Franklin Delano

Roosevelt.

And

so I did. With Daniel Aaron's expert guidance, a design began to emerge.

Absorbing this diary - overwhelming in scope, yet delicate in nature -

was like plunging head first into a frigid pool. Daunted at first by its

sheer size (1,600pages even in its abridged form), I swam on, pulled

forward through each entry by the emerging voice. Almost every one

hinges upon Inman's opinions on everything from the price of soap to the

bloated reputation of one of his favourite enemies, Franklin Delano

Roosevelt.

Inman spared no one his poisoned pen, even his wife of

40 years, Evelyn Yates Inman. She emerges, for me, as one of the great

female figures in contemporary non-fiction. Her long-suffering role of

nursemaid, cajoler, co-conspirator and loyal friend to her ill-chosen

man brings to the diary a much-needed domestic reality without which it

would lose much of its appeal. Arthur's opinion of her, alternately

scornful and full of praise, chronicles one of the most strangely

functional marriages, real or imagined, ever set down on paper.

"What

a pale personality Evelyn has, so many predictable little gestures of

speech and action. And homely as a stump fence in the

dark... Is it possible to live with any degree of closeness to someone

and not hate them on occasion?"

"What

a pale personality Evelyn has, so many predictable little gestures of

speech and action. And homely as a stump fence in the

dark... Is it possible to live with any degree of closeness to someone

and not hate them on occasion?"

When Evelyn showed Arthur love, performed some useful

function for him or simply accepted him for the difficult but lovable

creature he had become, his views on her changed.

"Ambivalence aside, Evelyn is the sweetest child in

all the world. I am, in fact, of the humble opinion that my wife is a

treasure among treasures, the hub of the wheel of my existence. I guess

I love her more than I had any idea. Admitting it is not unlike having a

tooth pulled. Funny thing, love."

"Ambivalence aside, Evelyn is the sweetest child in

all the world. I am, in fact, of the humble opinion that my wife is a

treasure among treasures, the hub of the wheel of my existence. I guess

I love her more than I had any idea. Admitting it is not unlike having a

tooth pulled. Funny thing, love."

After beginning a correspondence with Aaron in the

mid-1980s, I slowly began to see the dramatic potential hidden in the

elephantine folds of the diary. After several years of spadework,

writing outline after outline to try to create some definable storyline,

in the mid-90s I had to actually tackle the job. By chance I came upon

the idea of setting the play during the last few days of Inman's life.

Hanging this vast memory piece on some kind of structure seemed

essential to keep the attention of an audience, for whom Arthur's

taciturn nature and outrageous opinions might be enough to drive them

from their seats. Likewise, any attempt to oversanitise the man would be

to ignore one of Arthur's most strenuous demands of any "editor of

the future".

After beginning a correspondence with Aaron in the

mid-1980s, I slowly began to see the dramatic potential hidden in the

elephantine folds of the diary. After several years of spadework,

writing outline after outline to try to create some definable storyline,

in the mid-90s I had to actually tackle the job. By chance I came upon

the idea of setting the play during the last few days of Inman's life.

Hanging this vast memory piece on some kind of structure seemed

essential to keep the attention of an audience, for whom Arthur's

taciturn nature and outrageous opinions might be enough to drive them

from their seats. Likewise, any attempt to oversanitise the man would be

to ignore one of Arthur's most strenuous demands of any "editor of

the future".

"One day you will know my world more intimately

than you do your own, will have mapped its texture, its Chinese box

construction. Should you choose to emphasize my whiny, rotten qualities,

so be it. If I am made out as some kind of genius of solitude, I will

likewise go along. But if you attempt to nicen me up I will come back as

a ghost and seek revenge on you as one who has cheated me of my rightful

place in history."

Not

wanting this curse upon my head, I have tried to present the man warts

and all. I have turned lengthy diary entries into what I hope are cogent

scenes, rendering monologues into credible dialogue between what were

once living, breathing people. Naturally, what is on display in Camera

Obscura is but a fragment of these people's lives. One would need scores

of Forsyte Sagas to even begin to encompass the girth of what Inman left

behind. In this incarnation of the play, however, brevity is a very good

thing.

Not

wanting this curse upon my head, I have tried to present the man warts

and all. I have turned lengthy diary entries into what I hope are cogent

scenes, rendering monologues into credible dialogue between what were

once living, breathing people. Naturally, what is on display in Camera

Obscura is but a fragment of these people's lives. One would need scores

of Forsyte Sagas to even begin to encompass the girth of what Inman left

behind. In this incarnation of the play, however, brevity is a very good

thing.

· Camera Obscura is at the Almeida Rehearsal

Room, London N1, from Monday. Box office: 020-7359 4404.

For the Guardian Online article

"DIARY OF A NOBODY" by Lorenzo DeStefano, click

here

For the London Observer review "The turtle, the librarian and the

Barbie Dolls", click

here

For the London Independent reviews "In Bed with Arthur Inman",

click here

For the British Medical Journal review, click here

On the face of it, this would not seem like a subject

for a play: static, verbose, disagreeable. But Camera Obscura is

a fantastic

piece, written by Lorenzo DeStefano and meticulously directed by

Jonathan Miller.

On the face of it, this would not seem like a subject

for a play: static, verbose, disagreeable. But Camera Obscura is

a fantastic

piece, written by Lorenzo DeStefano and meticulously directed by

Jonathan Miller. I

revelled, too, in the language, which is as agile as Inman himself is

immobile. He hazards weird, decadent generalisations. He seldom has an

ordinary response to anything. He looks like a cross between a turtle

and Oscar Wilde, beached high on his hospital bed with whisky, pink

pills, girls who resemble Barbie dolls and an uncanny wife - Evelyn - as

his companions.

I

revelled, too, in the language, which is as agile as Inman himself is

immobile. He hazards weird, decadent generalisations. He seldom has an

ordinary response to anything. He looks like a cross between a turtle

and Oscar Wilde, beached high on his hospital bed with whisky, pink

pills, girls who resemble Barbie dolls and an uncanny wife - Evelyn - as

his companions. The

tables have been turned on the excellent actor Peter Eyre. Earlier this

year, as Kenneth Tynan paying court to Louise Brooks in Smoking with

Lulu, he played the visitor of a legendary recluse. Now, in Lorenzo

DeStefano's fascinating play Camera Obscura, he plays the

legendary recluse who is being visited, skilfully switching from bedside

to in-bed manner.

The

tables have been turned on the excellent actor Peter Eyre. Earlier this

year, as Kenneth Tynan paying court to Louise Brooks in Smoking with

Lulu, he played the visitor of a legendary recluse. Now, in Lorenzo

DeStefano's fascinating play Camera Obscura, he plays the

legendary recluse who is being visited, skilfully switching from bedside

to in-bed manner. The show is based on the real-life diaries of Arthur

Crew Inman (1895-1963), a moneyed American who made a kind of art form

of his phobias (to light, noise, John F Kennedy etc) and took the

principle

of room service to quite extraordinary lengths. Unwilling to leave his

darkened apartment in the Garrison Hall hotel, in Boston, where he had

bought all the neighbouring flats in a doomed effort to eliminate

disturbance, he advertised in the press for "talkers" to tell

him the story of their life. Some of the females who responded were

fondled; others had full sex. The diaries therefore became an informal

and unpublished Kinsey report avant la lettre. His live-in wife

put up with his behaviour.

The show is based on the real-life diaries of Arthur

Crew Inman (1895-1963), a moneyed American who made a kind of art form

of his phobias (to light, noise, John F Kennedy etc) and took the

principle

of room service to quite extraordinary lengths. Unwilling to leave his

darkened apartment in the Garrison Hall hotel, in Boston, where he had

bought all the neighbouring flats in a doomed effort to eliminate

disturbance, he advertised in the press for "talkers" to tell

him the story of their life. Some of the females who responded were

fondled; others had full sex. The diaries therefore became an informal

and unpublished Kinsey report avant la lettre. His live-in wife

put up with his behaviour. The photo of a testy-looking, toothbrush-moustached

Inman in the programme suggests a peppery, wired-up individual.

Eschewing impersonation, Peter Eyre converts the character into a great

tragicomic creation, his

demeanour reminding you more of the flabby Wilde, and his seductively

low-key Southern drawl, of a Tennessee Williams faded belle. The

dimpling, little-boy bids for pathos are as outrageously manipulative as

his innocent-seeming curiosity when he's pruriently quizzing his lady

visitors about the precise sensations felt during the female orgasm.

There's something at once floppily invertebrate and strong-willed about

this whisky-swigging, politically bigoted self-made invalid who takes

such a calculatedly childish delight in tape-recording every

embarrassing session. To be goosed by him would be like being molested

by a tenacious blancmange.

The photo of a testy-looking, toothbrush-moustached

Inman in the programme suggests a peppery, wired-up individual.

Eschewing impersonation, Peter Eyre converts the character into a great

tragicomic creation, his

demeanour reminding you more of the flabby Wilde, and his seductively

low-key Southern drawl, of a Tennessee Williams faded belle. The

dimpling, little-boy bids for pathos are as outrageously manipulative as

his innocent-seeming curiosity when he's pruriently quizzing his lady

visitors about the precise sensations felt during the female orgasm.

There's something at once floppily invertebrate and strong-willed about

this whisky-swigging, politically bigoted self-made invalid who takes

such a calculatedly childish delight in tape-recording every

embarrassing session. To be goosed by him would be like being molested

by a tenacious blancmange. Yet the play and the performance help you to see why so

many people remained loyal to him – not least his wife, whose

oscillation between exasperated affection and the desperate desire for

some freedom and dignity is beautifully captured by Diana Hardcastle.

The hypochondriac's gently insistent air of total entitlement would very

quickly, you feel, enslave anyone without his paradoxical strength of

character. But that manner covers a terrible

pathos.

Yet the play and the performance help you to see why so

many people remained loyal to him – not least his wife, whose

oscillation between exasperated affection and the desperate desire for

some freedom and dignity is beautifully captured by Diana Hardcastle.

The hypochondriac's gently insistent air of total entitlement would very

quickly, you feel, enslave anyone without his paradoxical strength of

character. But that manner covers a terrible

pathos. The play is shaped in the life-in-the-day-of format, and

it happens to be the day, in 1963, on which he took his own life. The

consequences of his warped manner of existence crowd in on him. Through

a succession of encounters, which the expert shading of Jonathan

Miller's production prevents from ever feeling like a desultory straggle

of

visits, Inman makes some painful discoveries. He forces his wife into

revealing her 30-year affair with his doctor and friend, Cyrus Pike

(Jeff Harding). His sinister, Orton-esque Dutch manservant (Richard

Brake) turns out to have passed on one of the incriminating diaries to

his landlords, raising the threat of eviction from his

cocooned redoubt. And not just the living come to pay their disrespects.

Causing him to curl up in a foetal heap, his cotton-baron father pops

back from the dead to remind Inman of his vain attempts to become a

poet, derisively quoting the awful doggerel and its vicious reviews.

The play is shaped in the life-in-the-day-of format, and

it happens to be the day, in 1963, on which he took his own life. The

consequences of his warped manner of existence crowd in on him. Through

a succession of encounters, which the expert shading of Jonathan

Miller's production prevents from ever feeling like a desultory straggle

of

visits, Inman makes some painful discoveries. He forces his wife into

revealing her 30-year affair with his doctor and friend, Cyrus Pike

(Jeff Harding). His sinister, Orton-esque Dutch manservant (Richard

Brake) turns out to have passed on one of the incriminating diaries to

his landlords, raising the threat of eviction from his

cocooned redoubt. And not just the living come to pay their disrespects.

Causing him to curl up in a foetal heap, his cotton-baron father pops

back from the dead to remind Inman of his vain attempts to become a

poet, derisively quoting the awful doggerel and its vicious reviews. Why

bother, one could ask, with the rantings of a semi-invalid holed up in a

crumbling apartment hotel in a dying American city? What use are his

unsolicited opinions on world affairs, his ambitions for literary

immortality, his calcified Victorian ideas on race and natural

selection, his obsession with young girls? In the case of Arthur Crew

Inman, I found his ramblings very useful indeed - once I had overcome my

initial revulsion in order to look further into his self-made shadow

land.

Why

bother, one could ask, with the rantings of a semi-invalid holed up in a

crumbling apartment hotel in a dying American city? What use are his

unsolicited opinions on world affairs, his ambitions for literary

immortality, his calcified Victorian ideas on race and natural

selection, his obsession with young girls? In the case of Arthur Crew

Inman, I found his ramblings very useful indeed - once I had overcome my

initial revulsion in order to look further into his self-made shadow

land.

I first encountered the 17 million-word diary of this

transplanted resident of Boston in 1985, the year Harvard University

Press published a two-volume set entitled The Inman Diary: A Public and

Private Confession. Edited over a seven-year period by Daniel Aaron, a

professor of American literature at Harvard, Inman's diary easily

qualifies as the longest ever written by an American and perhaps by any

citizen of any land.

I first encountered the 17 million-word diary of this

transplanted resident of Boston in 1985, the year Harvard University

Press published a two-volume set entitled The Inman Diary: A Public and

Private Confession. Edited over a seven-year period by Daniel Aaron, a

professor of American literature at Harvard, Inman's diary easily

qualifies as the longest ever written by an American and perhaps by any

citizen of any land.

Some

would say that this is inordinately high company for a scribbling nobody

to keep, even in his own mind. And yet, taken as a whole, The Inman

Diary stands up quite well alongside those great chroniclers. While one

quickly tires of his endless hypochondriacal moanings - "right

thumb sprained, coccyx badly bruised, both arms a constant useless

agony. What a bruised, squirming semblance of a thing I am" - it is

the truly democratic nature of Inman's diary that most impresses me.

Some

would say that this is inordinately high company for a scribbling nobody

to keep, even in his own mind. And yet, taken as a whole, The Inman

Diary stands up quite well alongside those great chroniclers. While one

quickly tires of his endless hypochondriacal moanings - "right

thumb sprained, coccyx badly bruised, both arms a constant useless

agony. What a bruised, squirming semblance of a thing I am" - it is

the truly democratic nature of Inman's diary that most impresses me.

By including the hopes and dreams of the anonymous

shopgirls and clerks and travelling salesmen who responded to

his lure in great numbers, Inman broadened the scope of his work without

a thought for social rank or educational accomplishment. What interested

him most was a cracking good story well told, the effluvia of lives he

could barely imagine on his own.

By including the hopes and dreams of the anonymous

shopgirls and clerks and travelling salesmen who responded to

his lure in great numbers, Inman broadened the scope of his work without

a thought for social rank or educational accomplishment. What interested

him most was a cracking good story well told, the effluvia of lives he

could barely imagine on his own.

And

so I did. With Daniel Aaron's expert guidance, a design began to emerge.

Absorbing this diary - overwhelming in scope, yet delicate in nature -

was like plunging head first into a frigid pool. Daunted at first by its

sheer size (1,600pages even in its abridged form), I swam on, pulled

forward through each entry by the emerging voice. Almost every one

hinges upon Inman's opinions on everything from the price of soap to the

bloated reputation of one of his favourite enemies, Franklin Delano

Roosevelt.

And

so I did. With Daniel Aaron's expert guidance, a design began to emerge.

Absorbing this diary - overwhelming in scope, yet delicate in nature -

was like plunging head first into a frigid pool. Daunted at first by its

sheer size (1,600pages even in its abridged form), I swam on, pulled

forward through each entry by the emerging voice. Almost every one

hinges upon Inman's opinions on everything from the price of soap to the

bloated reputation of one of his favourite enemies, Franklin Delano

Roosevelt.

"What

a pale personality Evelyn has, so many predictable little gestures of

speech and action. And homely as a stump fence in the

dark... Is it possible to live with any degree of closeness to someone

and not hate them on occasion?"

"What

a pale personality Evelyn has, so many predictable little gestures of

speech and action. And homely as a stump fence in the

dark... Is it possible to live with any degree of closeness to someone

and not hate them on occasion?"

"Ambivalence aside, Evelyn is the sweetest child in

all the world. I am, in fact, of the humble opinion that my wife is a

treasure among treasures, the hub of the wheel of my existence. I guess

I love her more than I had any idea. Admitting it is not unlike having a

tooth pulled. Funny thing, love."

"Ambivalence aside, Evelyn is the sweetest child in

all the world. I am, in fact, of the humble opinion that my wife is a

treasure among treasures, the hub of the wheel of my existence. I guess

I love her more than I had any idea. Admitting it is not unlike having a

tooth pulled. Funny thing, love."

After beginning a correspondence with Aaron in the

mid-1980s, I slowly began to see the dramatic potential hidden in the

elephantine folds of the diary. After several years of spadework,

writing outline after outline to try to create some definable storyline,

in the mid-90s I had to actually tackle the job. By chance I came upon

the idea of setting the play during the last few days of Inman's life.

Hanging this vast memory piece on some kind of structure seemed

essential to keep the attention of an audience, for whom Arthur's

taciturn nature and outrageous opinions might be enough to drive them

from their seats. Likewise, any attempt to oversanitise the man would be

to ignore one of Arthur's most strenuous demands of any "editor of

the future".

After beginning a correspondence with Aaron in the

mid-1980s, I slowly began to see the dramatic potential hidden in the

elephantine folds of the diary. After several years of spadework,

writing outline after outline to try to create some definable storyline,

in the mid-90s I had to actually tackle the job. By chance I came upon

the idea of setting the play during the last few days of Inman's life.

Hanging this vast memory piece on some kind of structure seemed

essential to keep the attention of an audience, for whom Arthur's

taciturn nature and outrageous opinions might be enough to drive them

from their seats. Likewise, any attempt to oversanitise the man would be

to ignore one of Arthur's most strenuous demands of any "editor of

the future".

Not

wanting this curse upon my head, I have tried to present the man warts

and all. I have turned lengthy diary entries into what I hope are cogent

scenes, rendering monologues into credible dialogue between what were

once living, breathing people. Naturally, what is on display in Camera

Obscura is but a fragment of these people's lives. One would need scores

of Forsyte Sagas to even begin to encompass the girth of what Inman left

behind. In this incarnation of the play, however, brevity is a very good

thing.

Not

wanting this curse upon my head, I have tried to present the man warts

and all. I have turned lengthy diary entries into what I hope are cogent

scenes, rendering monologues into credible dialogue between what were

once living, breathing people. Naturally, what is on display in Camera

Obscura is but a fragment of these people's lives. One would need scores

of Forsyte Sagas to even begin to encompass the girth of what Inman left

behind. In this incarnation of the play, however, brevity is a very good

thing.